Tides: Everything You Need to Know

Words by Max Campbell

One of my favourite swimming spots lies at the top of a picturesque tidal creek. It’s special because of the scenic woodland walk, the few people who know about it, and mostly because you can only swim there on occasion.

It needs a sizeable high tide, above five meters is best. And when the tides align it’s a dream, with a nice, uncomplicated entrance of a grassy quay, and enough water to keep you far from the sticky mud below. Placid oak trees reach down and caress the polished surface of the river and there’s scarcely a sign of humanity to be seen.

The rest of the time, swimming here is impossible. The river banks are made of a soft silt, and it’s impossible to exit the water without becoming caked to your knees in mud. And it’s not just a light bit of dirt. This is a thick, black sediment – an accumulation of soft sand and rotten trees, that’s not coming off without a shower. So you find yourself walking the mile walk back to the car barefoot.

The rare swims at this spot demonstrate how the tides can produce moments of fleeting serenity. They can also be extremely dangerous and potentially deadly. As a wild swimmer, especially someone who swims regularly in the sea, it’s vital to have some understanding of what tides are and how they work. This blog will explain how tides are generated, why they are so predictable, and common risks that come as a consequence of these gigantic movements of water.

At some river locations, swimming is only possible at the highest of tides.

What are tides?

Tides are the biggest ocean waves we experience on planet earth. High Water (HW) is the highest point (or crest) of the wave and Low Water (LW) is the lowest point (or trough). The rhythmic rise and fall that we experience at the coastline is simply the propagation of this long-period wave, where the crest and trough of one wave passes, to be followed by the crest of the next wave. Typically, there are two high waters and two low waters in any one day, and both HW’s are separated by a time period of 12 hours and 25 minutes. The difference in height between LW and HW is called the tidal range.

As well as the rhythmic rising and falling of sea-level, the passing of the tide can also manifest as horizontal currents. These currents arise as the tidal wave moves around coastlines and enters estuaries. These currents are bi directional, meaning they flow one way with the incoming (or flood) tide, and in the opposite direction with the outgoing (or ebb) tide. The strongest currents typically occur three hours before and after both HW and LW, when the tide is moving at its quickest. During HW and LW, the tidal currents are often weak, and this period of time is called ‘slack water’.

Misjudge the tides and you may end up with very muddy feet

What causes the tides?

Ocean tides arise from the gravitational attraction of the sun and the moon, both of which possess a Tidal Generating Force (TGF). Despite the sun being massively larger than the moon, its TGF is about half the size of the moon, as a result of it being much further away.

As the moon orbits Earth, it's followed by the bulging tidal wave beneath it, drawn upwards by its gravitational attraction. It takes the moon 24 hours and 50 minutes to orbit earth, and each day one of the two HW’s we experience is a result of the moon's gravitational attraction.

The second HW is at the opposite end of the planet to the moon’s gravitational bulge, and it’s a result of a centrifugal force. This Centrifugal force is the same force that works to throw you off a spinning merry-go-round at the park. The Earth and the Moon combine to form the Earth-Moon system, which spins around a point called the centre of rotation. A second tidal bulge, at the opposite end of the planet, is the result of this centrifugal force.

So a single point will experience two HW’s a day. One as a result of the gravitational attraction of the moon, and the second as a result of the centrifugal force due to the rotation of the Earth-Moon system.

Without tides, Cornwall would be without its epic selection of tidal pools

Spring and Neap Tides

A solar day is 24 hours long, this is because it takes earth 24 hours to complete an entire rotation on its axis. A lunar day is 24 hours and 50 minutes long. The moon revolves around the Earth in the same direction that it rotates, therefore it takes an extra 50 minutes for the earth to ‘catch up’.

The difference in time between a lunar day and a solar day results in a cycle where the sun and moon vary from being in alignment with the earth, to being at right angles to each other. The result is that in two weeks we experience both Spring Tides (high tidal range) and neap tides (low tidal range).

Another factor that adds to variation of tidal range is the elliptical orbit of the moon around the sun. During periods where the moon is particularly close, and in alignment with the sun, we experience ‘King Tides’, this is when the tidal range is at its highest.

A line of seaweed deposited on the shoreline indicates the water level at high tide

Why are tides dangerous?

There are two main dangers that tides present. The first is a result of the tidal range, and the second is a result of the tidal currents.

When swimming in the sea, it’s always wise to check the tide tables before going to the beach. A common mistake is to venture off at low water to find a secluded section of beach that soon becomes inaccessible as a result of the rising tide. It’s also very easy to leave your possessions on the beach, only to return to find them soaked by the rising sea level. A consistent line of seaweed deposited on on the shoreline at the top of the beach is often a good indicator of the water level at HW.

The second, more dangerous, consequence of tides are the strong and unrelenting tidal currents that come with the passing of high and low water. These are often particularly strong in rivers and estuaries, where water is forced into and out of a basin. It’s possible to identify tidal currents, as they result in a swirling, choppy sea surface. Tidal currents are strongest at mid-tide, and in some parts of Cornwall they can reach speeds of several knots (1 knot = 1.15 mph).

In Cornwall, tidal range is highest on the north coast, and it increases as you head west. If you’re swimming in North Cornwall, make sure to pay extra attention to the state of the tide. Tidal currents will be present in all rivers and estuaries in Cornwall, so make sure to study the surface for moving water before swimming in any estuary or river.

It’s locations like this, where water is ‘squeezed’ through a narrow gap, that tidal currents can be particularly strong

How to read the tides

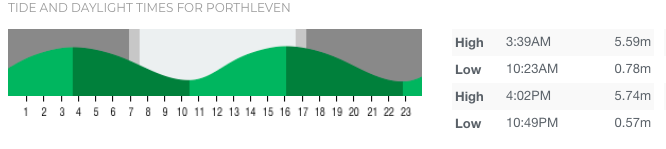

There are many websites that provide tide tables, or you can even purchase a handy, pocket size book from most surf shops. We prefer Magic Seaweed, as it provides information on wind and swell, as well as tide tables. The table will provide a time for HW and LW, as well as the height of the tide in meters. The tidal range is the difference in height between the height of the tide at HW and LW, which varies around the Cornish Coastline. As a rule of thumb, spring tides are when the tidal range is bigger than 5m on the south coast, and bigger than 6m on the north coast.

Tide times on Magicseaweed, showing the time of HW and LW, as well as the height of each

More about tides

The above summarises the basic mechanics behind how tides work. We’ve only really scratched the surface, and there’s a lot more that goes into the daily rise and fall of sea-level. If you have any questions about tides, or have any spot specific questions, then feel free to write to us at wildswimmingcornwall@gmail.com.

Safe swimming!

If you enjoyed this blog, why not sign up to our newsletter?

And if you know someone else who would enjoy it, please share it with them via email or social media.