How to stay safe whilst wild swimming

The most important safety aspect of wild swimming is to know your limits. The ocean can be unforgiving and demands respect.

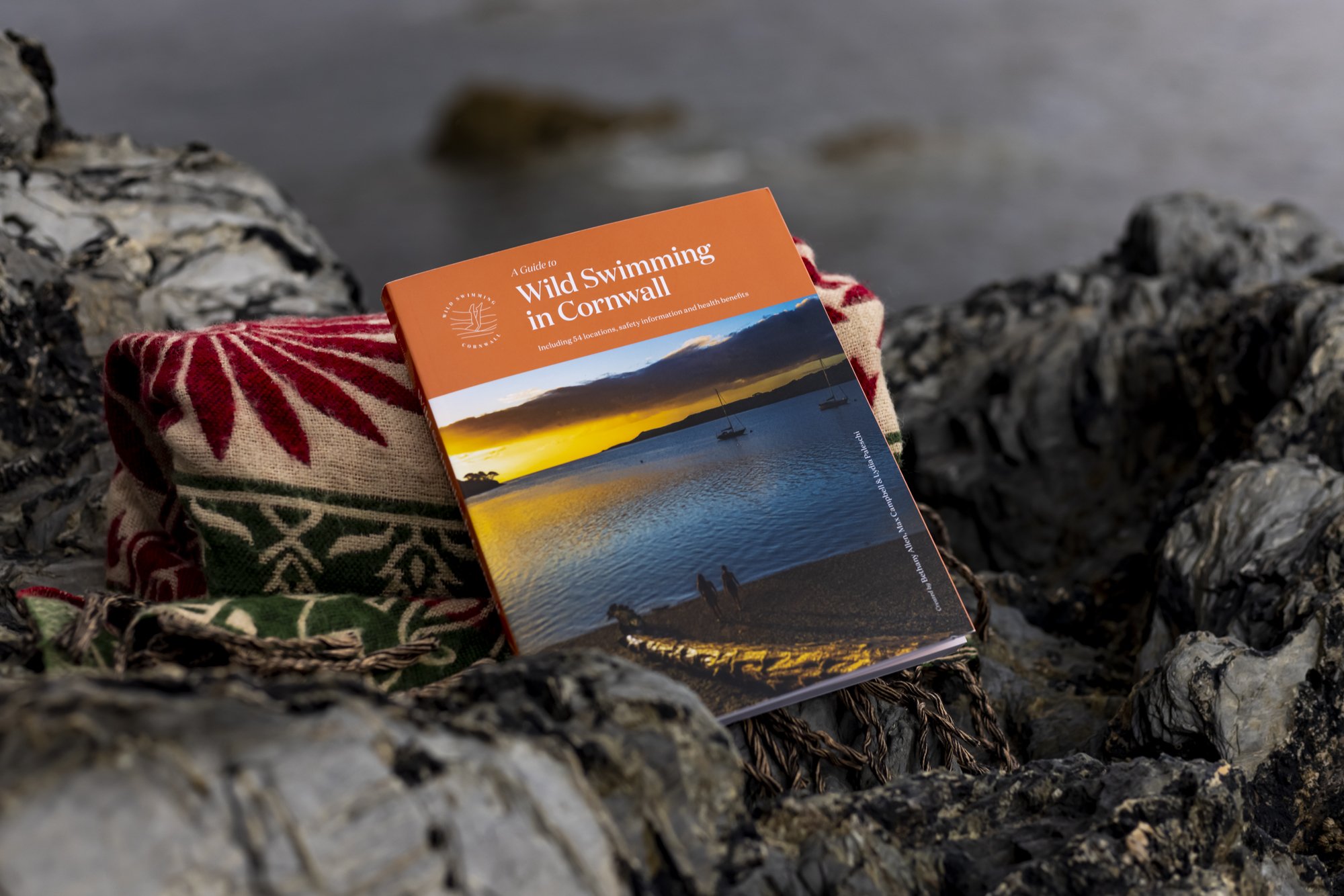

For location specific safety information, our book A Guide to Wild Swimming in Cornwall provides details on what to look out for at our favourite swimming spots around the county.

For more general guidance on ocean safety, we have provided detailed information on how to stay safe whilst wild swimming further down this page.

An introduction to safety

Unlike a swimming pool, the ocean is a large, uncontrolled environment, and therefore the preparation for any swim requires careful thought and consideration of all the potential risks. We have made a list of the main dangers associated with wild swimming in Cornwall, and by familiarising yourself with them, you can plan to minimise risk prior to any wild swimming trip.

Below is a list of our key health and safety guidelines

It’s always safer to swim with others. If you do decide to go by yourself, be sure to tell somebody where you’re going;

If you are new to sea swimming, then we recommend you start with beaches that are lifeguarded, and refrain from venturing far out of your depth;

Always wear the appropriate clothing. If you’re planning on staying in for more than 10-15 minutes, it may be best to wear a wetsuit (in winter it is definitely best to wear a wetsuit or not stay in longer than 5 minutes), and always ensure that you have warm clothes to change back into;

Always consider the depth of the water, the current, tides, the surf conditions, the seabed, as well as entry and exit points, before entering the water;

Don’t swim if you are intoxicated in any way;

Is there a risk from the cleanliness of the water, or a risk from marine animals (e.g. jellyfish)?

Make sure that you are always visible in the water;

Familiarise yourself with the procedures you must take in an emergency (either attracting the attention of a lifeguard, or calling 999 if no lifeguards are present).

The Marine Environment: What to consider before a wild swim

Expand each of the sections below to learn more about how to stay safe whilst wild swimming.

+ Temperature

Water temperature is the most important factor in dictating the length of your swim. Cornish sea water temperatures can drop as low as 7 degrees in winter, and reach highs of 18 degrees in summer. Cold water can be dangerous over both short and longer time periods, and the two main risks associated with cold water are cold water shock and hypothermia.

Sudden immersion in cold water can bring on a sharp intake in breath, an increase in breathing rate and an increase in blood pressure, this is called cold water shock. This effect can cause complications for anyone with underlying heart conditions, as well as the added risk of inhaling seawater from the sudden need to breathe. To avoid cold water shock, enter the water slowly, and refrain from submerging your head until you have fully adjusted to the water temperature.

Over longer time periods, the risk of hypothermia grows. Immersion in cold seawater will cause your core body temperature to drop, as the body is losing heat faster than it can be generated. A drop in your core body temperature will compromise your heart, nervous system and other organs, and if left untreated, will lead to loss of consciousness and heart failure. The amount of time you can spend in the water will depend on the sea temperature, your body size and your experience with cold water. We suggest you start off with short swims to determine your limits, and if you begin to experience shivering, drowsiness, shallow breathing or confusion, then exit the water and warm up.

You can still experience the effects of hypothermia after leaving the water, as your body continues to circulate cold blood. Often, you will start to really feel the effects of hypothermia after leaving the water, which is why it’s important to get dressed as soon as you can. To minimise the risk of hypothermia, be mindful of how long your body can withstand the cold, and always ensure you have plenty of layers to change back into.

To check the current air and seawater temperature, visit www.magicseaweed.com.

+ Waves

Some of Cornwall’s wild swimming spots are directly exposed to the Atlantic. Often, swimming at these locations requires the negotiation of breaking waves. Swimming within the surf isn’t easy - the ocean can be forceful, and being held under the water by a breaking wave is a very real threat. Therefore, we suggest that only experienced sea swimmers visit exposed spots, and that they should refrain from entering the water if the waves are higher than one meter (three feet).

The main risk associated with breaking waves are rip currents. A breaking wave will push seawater into the beach, causing a ‘pile up’ in the shallows. Naturally, water will always seek its own level, and the result is a strong, river-like flow, which runs from the shallows back out to sea. Rip currents are often clearly visible as a region of disturbed, discoloured water between two areas of breaking waves. If you can identify a rip current, and the beach is un-lifeguarded, it’s best to stay out of the water completely. Lifeguarded beaches will use red and yellow flags to define the safe swimming area, and it’s important to remain within the flags to avoid the risk of rip currents.

If you do find yourself struggling against a rip current, do not swim against the flow. It’s very difficult to swim against the current, and ultimately you will expend a lot of energy without covering much ground. The way to navigate out of a rip current is by swimming perpendicular to the direction of flow (i.e. parallel to the shoreline). By doing this, you will remove yourself from the center of the current and swim into a region of relatively still water. Once you are out of the rip current, you should be able to swim back to shore. Rip currents are ubiquitous with breaking waves, and their risk can be reduced by avoiding spots with surf, not venturing out of your depth, and only visiting lifeguarded beaches. They are a very real threat, and Cornish RNLI lifeguards are faced with rescuing inexperienced swimmers from rip currents on a daily basis.

You can find more information on rip currents, including images here.

You can check the current surf conditions at www.magicseaweed.com.

+ Tides and Currents

As well as surf, much of the water movement in the Cornish coastal marine environments is a result of the tides. The South West of England experiences one of the largest tidal ranges in the world, and big tides in Cornwall can exceed six meters. The tides follow a semi-diurnal frequency, which means there are two high tides and two low tides a day, with high water and low water being around 6 hours apart. The rhythmic rise and fall of seawater that we see, is a complex result of the Moon orbiting the Earth which orbits the sun. Checking the tide times is an essential part in the preparation for any sea swim. As swimmers, the tide can affect us in two ways, each bringing their own relevant risks that need to be considered.

The most obvious effect of the tide is the physical rising and falling of the sea level. By considering the state of the tide, and planning ahead, you can avoid the circumstance of being blocked or trapped by the rising tide. It is also important to consider how the changing tide will affect your entry and exit points. A spot with a easy sandy entrance may be rocky at low tide, and vice versa, a spot that’s sandy at low tide may be inaccessible at high tide.

The second, less visible effect of the tide is the tidal current. The tide is essentially a large, slow wave, that moves its way along the coastline, inducing localised currents that reverse direction every six hours. The tidal currents will be strongest at mid-tide (in between high water and low water), and will be especially strong around headlands, narrow channels and in estuaries. Swimming into a tidal current can result in a swimmer being swept away from their entrance point, and as the water is often still, it can be difficult to determine the strength of the tidal current. Before swimming at any tidal spot, make sure to check the tide times, and often you will need to plan your swim around them. Also be weary of the local effect of tidal currents, and avoid venturing too far out if there is potential for strong tidal currents.

You can learn about tides here.

Information on tide times can also be found on www.magicseaweed.com.

+ Topography and Bathymetry

Dangers can also originate from the structure of the seabed and the surrounding cliffs. Avoid any dangerous access routes, and always consider what lies beneath the surface. Dramatic cliffs and rocky coastlines give Cornwall its rugged beauty, however they can also present complications for wild swimming. If you are just starting out, stick to spots with easy access, and clear points of entry and exit into the water.

+ Water Quality

Generally the water quality is good in Cornwall. After periods of high rainfall, seawater can become contaminated with farmland or urban runoff. There is also the risk of sewage overflows releasing raw, untreated human waste into the ocean. The Safer Seas Service app, provided by Surfers Against Sewage, is a free online service that alerts users in real-time of the risk of untreated human sewage and other pollution affecting water quality.

Be mindful of both these risks, and if you find something that should be reported then call the pollution reporting hotline (0800 80 70 60).

Marine plastic is a growing global concern. The sheer volume of plastic in the marine environment is terrifying. We aim to have an overall positive impact on the locations we visit, so as well as keeping hold of our own waste, we try to remove as much plastic from the marine environment as possible. Consider taking an extra bag that you can use to collect any plastic you find, which can then either be discarded properly or recycled.

+ Marine Animals

There are only a few marine animals in Cornwall that can cause harm to humans. Most will inflict a sting, resulting in mild to moderate pain. If you feel like you’ve been stung by something, it’s important to leave the water, as there is a possibility of venom leading to a severe allergic reaction and anaphylactic shock.

Weever fish are the most common stinging creature found in Cornish waters. They are found in soft sand, and bury themselves so that only a small stinger on their back is exposed. If you stand on one, you will feel a sharp spike beneath your foot. Shortly after, you may feel a throbbing pain around the sting, which can often be quite intense. To treat a weever fish sting, simply immerse your foot in a bucket of warm water. The heat will denature the protein in the sting, and the pain should begin to subside. The warmer the water, the quicker the pain will begin to ease, so it’s important to keep adding boiling water to the bucket, to bring the temperature up to as high as you can tolerate.

Jellyfish stings are the other common hazard. Instead of a defined sting, like a weever fish, jellyfish stings will show up over a larger area, and look similar to a rash. When treating a jellyfish sting, first thoroughly rinse the area with seawater (not freshwater). Next, use a bank card or tweezers to remove any tentacles still attached to the skin. Then, soak the area in hot water, using a flannel if the sting cannot be submerged. If needed, you can take paracetamol or ibuprofen to deal with the pain.

Both weever fish and jellyfish stings shouldn’t require hospital treatment, however if you start to experience symptoms of anaphylactic shock, you should seek medical attention immediately. Symptoms of anaphylaxis include a shortness of breath, feeling faint, an increased heart rate and anxiety.

Make a decision

Ultimately, the decision to enter the water is up to you. Local information can usually be found on an informative sign at the beach, or obtained from lifeguards if they are present. If you are aware of the risks listed above, then you should be able to make an assessment of the safety of each spot on a given day. If you are unsure about entering the water for any reason, we suggest you move to a safer spot, or even wait for a more suitable day. Whilst our aim is to encourage more people to participate in and reap the benefits of wild swimming, we do not wish to do so by encouraging people to compromise their safety. The information we post is for guidance purposes only and we accept no liability for what happens during the sea swims of others. For more information on this, please see our terms and conditions.